On the words we weaponize, and the boys we fail when we do

There’s a moment in basketball that doesn’t get talked about enough.

Not the buzzer-beater. Not the championship handshake. This one: a kid who rarely gets off the bench — maybe eight minutes of playing time all season — catches a pass in the final two minutes of a game his team is already winning comfortably, takes his shot, and it drops.

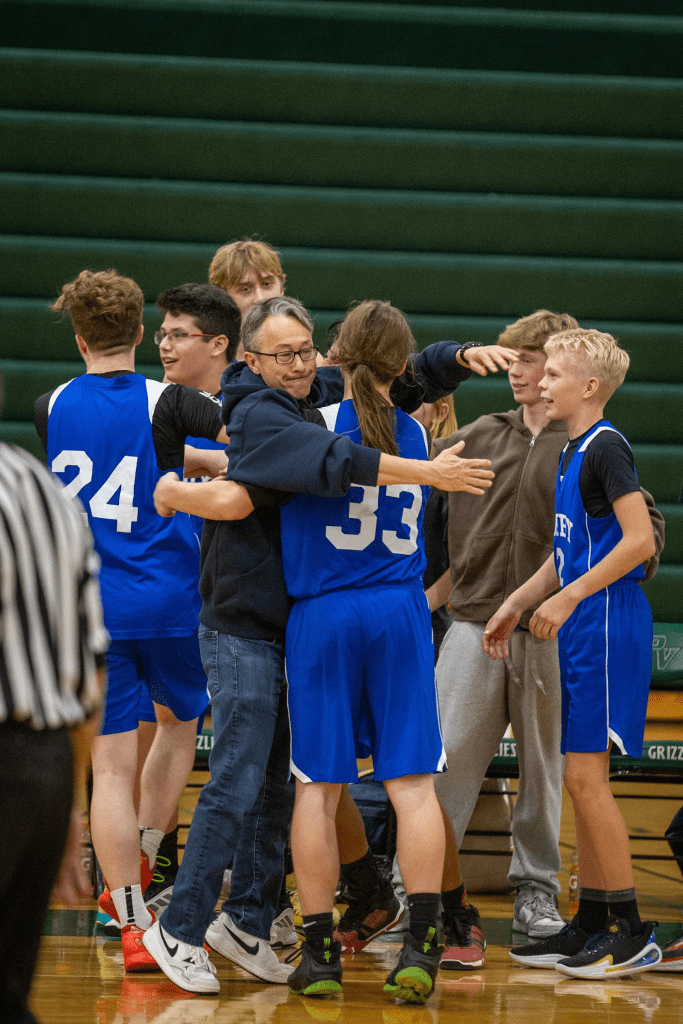

And his teammates lose their minds.

Not because the game was in doubt. Not because it changed anything on the scoreboard. But because they know what that basket means to him. They’ve watched him show up to every practice. They’ve seen him work. And in that moment, they chose to be loud about it.

That’s not aggression. That’s love. And it takes a particular kind of group — a psychologically safe one, actually — to produce it.

This is a story about that team. And about what happened next. But it’s really a story about words — the ones we reach for when we want to be right, and what it costs when we reach for the wrong ones.

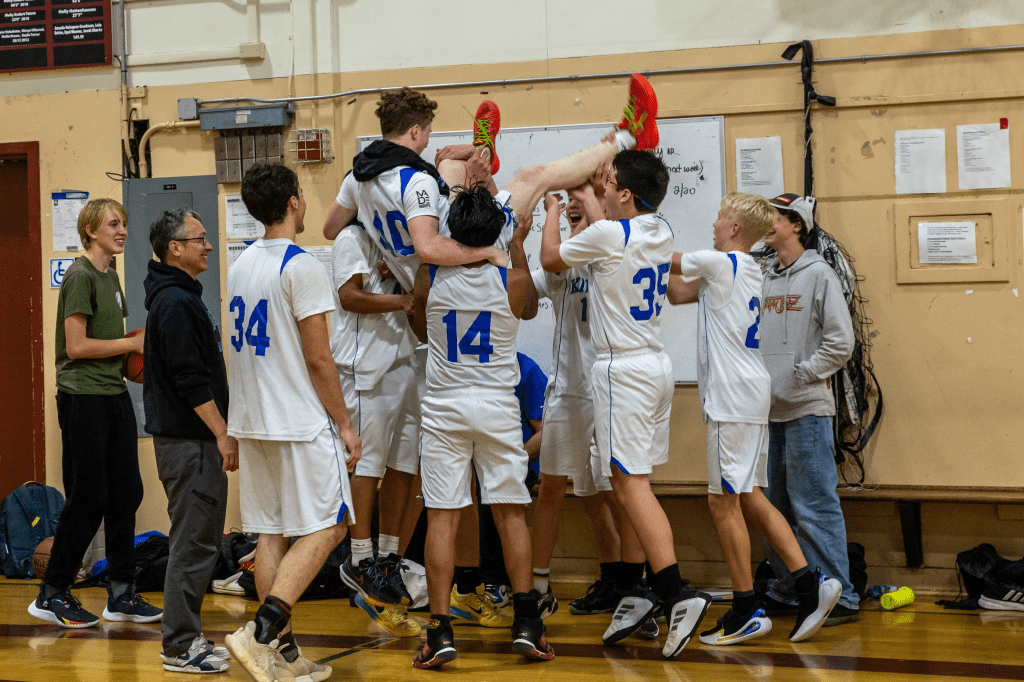

The boys on this basketball team weren’t supposed to win. They’d lost most of their games the year before. Same roster, mostly. They didn’t get taller or faster over the summer. What changed is harder to measure: they built something together. A culture. The kind where a teammate’s milestone feels like your milestone, where the bench erupts for a freshman’s seventh three-pointer because everyone in that gym understands they are watching something rare, and they want him to know they see it. The kind of theme that when something extraordinary happens, they can’t stay quiet about it.

This team won their league. First time in the school’s history. And the joy of it, the audible, visible, full-throated joy…. became a problem.

I want to be careful here, because the people who got involved weren’t acting in bad faith. Adults who care about kids sometimes see celebration and hear aggression, especially when it’s loud and male and coming from a team winning by a wide margin. That instinct; to protect, to intervene, comes from a real place.

But the word they reached for was toxic masculinity.

A senior was called in and told he needed more female role models. That he should sit out, hold his shots, make himself smaller. Not because he’d harmed anyone, but because his excellence had become conspicuous. This is a kid with specific goals for his final season, goals he’d held for years and could actually reach: league MVP and 1,000 career points. He was told he’d already achieved them, so he could slow it down. (I don’t think that is the mind of an athlete).

When another player tried to explain the why behind the celebration… the teammate’s milestone, the context, what the moment actually meant… the conversation didn’t happen. The word had already done its work.

One administrator even said it directly: if this were the first basket of the game, you’re doing it exactly right. She liked the how. She didn’t like the when. Which means what bothered her wasn’t the behavior itself, it was the score. The visibility of winning.

I’m a woman in tech. I’ve spent twenty years navigating environments where my ideas got credited to the man who repeated them, where my confidence read as abrasiveness and my directness as a problem to be managed. I know what toxic masculinity looks like. I’ve felt its weight.

So when I say that word was misapplied here, I’m not defending bad behavior with a jersey on it. I’m asking for precision. Because precision is what the word requires, and what these kids deserve.

Here’s what I’ve come to understand about real toughness, through years of watching my kids compete: performed strength looks like dominance. Real strength looks like this: a group of boys secure enough in themselves to celebrate each other without it threatening their own sense of standing. No ego transaction required. Just: you did something great, and I’m here for it.

That’s not what toxic masculinity produces. Toxic masculinity produces boys who can’t cheer for each other because another man’s success feels like a subtraction from their own. It produces silence in locker rooms. It produces the teammate who doesn’t pass, not the one who tracks whether his benchwarming friend has gotten his shot yet.

What we were watching in that gym was its opposite. And we called it by the wrong name.

A senior was called into the athletic director’s office and told he needed more female role models. That he should sit out, hold his shots, defer. Because winning by a large margin was making people uncomfortable. This is a kid with specific, achievable goals for his final season: league MVP and 1,000 career points. Goals he’d shared openly. Goals he’d worked years toward. He was told to abandon them. Not because he’d done anything wrong. Because his excellence had become inconvenient.

Another player tried to explain the why behind the celebration. The teammate’s milestone, the context, the meaning. He was yelled at in a hallway.

The AD said herself: if this were the first basket of the game, you’re doing it exactly right. She liked the how. She didn’t like the when. Which means what she was actually responding to was success itself; the discomfort of watching a team that wasn’t supposed to win, winning.

Here’s what I’ve come to understand about real toughness, through years of watching my kids compete and through my own working life:

Performed strength looks like dominance. Real strength looks like this: a group of boys secure enough in themselves to celebrate each other without it threatening their own sense of standing. No ego transaction required. Just: you did something great, and I’m here for it.

That’s not what toxic masculinity produces. Toxic masculinity produces boys who can’t cheer for each other because another man’s success feels like a subtraction from their own. It produces silence in locker rooms, not eruptions of joy. It produces the teammate who doesn’t pass, not the one who tracks whether his benchwarming friend has gotten his shot yet.

When we misidentify health as pathology, we don’t just get it wrong — we do damage. We teach boys that their exuberance is a problem. That their bonds are suspect. That winning requires apology. We hand them a diminished version of what sports can be, and we wonder later why so many young men are lonely.

There’s something else worth naming here.

Weeks before this, the school’s cross-country team — also boys, many of the same boys — won their league for the first time. Sent five runners to the postseason. Two earned first-team all-league honors. It was, by any measure, a historic achievement for a school that doesn’t have a reputation for athletic success.

The school gave athlete of the week that week to someone on a different team. Mentioned the cross-country title briefly, in passing, at the all-school meeting.

I don’t know what to make of the asymmetry except this: silence when boys succeed, intervention when boys celebrate. Neither response sees them clearly. One ignores them. One pathologizes them. Both fail them.

I want to be precise about this, because it matters:

The term “toxic masculinity” exists for a reason. It describes something real and harmful: the cultural pressure on men to perform dominance, suppress vulnerability, and measure their worth through control. It’s done serious damage, to women and to men. The people who coined it and who use it with care are describing something true.

But language is only as good as the precision with which we wield it. When we reach for a clinical, charged term to describe a teenager cheering for his teammate — when we deploy “toxic” to mean loud and winning– we do two kinds of harm at once.

The first is to the kids in front of us. We hand a teenager a diagnosis he doesn’t deserve. We tell him the thing he’s doing, celebrating his teammates, showing up with his whole self, letting his joy be visible, is pathological. He doesn’t have the context to push back on a word that carries that much cultural freight. So it lands. And it does what those words do when they land wrong: it teaches him to make himself smaller, to distrust his instincts, to wonder what’s wrong with him.

The second harm is quieter but just as real. Every time we use a serious word to win a minor argument, we wear it down. We make it harder for the next person who actually needs it. The person who is trying to name something true and damaging and can’t get anyone to listen because the word has been stretched to cover everything.

Words are how we make sense of the world together. When we use them to get our way instead of to tell the truth, we don’t just lose precision. We lose each other.

The question I keep coming back to isn’t about this team or this school. It’s bigger than that.

When we intervene in kids’ lives — and we should, when it’s warranted — are we doing it to actually help them? Or are we doing it to resolve our own discomfort, and reaching for the most powerful language available to justify the intervention? Those two things can look identical from the outside. But they’re not the same. One is about the kid. The other is about us.

There are boys who learn that dominance is strength, that vulnerability is weakness, that other people’s feelings don’t count. There are teams and locker rooms shaped by that, and the damage is serious and worth fighting. We should absolutely name it when we see it.

What we shouldn’t do is use that name to describe its opposite — a group of teenagers who have learned to genuinely care about each other, who celebrate each other’s achievements without it threatening their own sense of worth, who have built exactly the kind of culture we say we want for young men.

That’s not a diagnosis. That’s a success story.

My son is one of these kids. I’ve watched him become someone who cheers as hard for his teammate’s basket as he does for his own. I’ve watched him learn that being part of something larger than yourself isn’t a sacrifice; it’s the point. Sports gave him that. This team gave him that.

There’s a senior on this team playing his last season. He has goals he’s worked years toward and can actually reach. He showed up, put in the work, became the kind of player and teammate worth watching. What he deserved, in this final chapter, was to be seen clearly.

The words we use around young people shape what they believe about themselves. They’re listening more carefully than we think, and remembering longer than we expect.

Let’s make sure what they’re hearing is true.

We owe young people more than the projection of our discomforts onto their joy. We owe them adults who can tell the difference between a team celebrating its humanity and a team behaving badly. We owe them the chance to learn. Through competition, through loss, through the rare and extraordinary experience of winning together. What it actually means to be good to each other.

That’s not toxic masculinity.

That’s what we were hoping for all along.